When Yahweh Had a Bull’s Head: The Forgotten Faces of the Divine

How Early Israelites Saw God Differently—and Why It Still Matters

Many people today follow the laws from the early Hebrew Bible as if they were timeless mandates.

Yet these laws were written by people whose outer and inner worlds had more differences from ours than similarities.

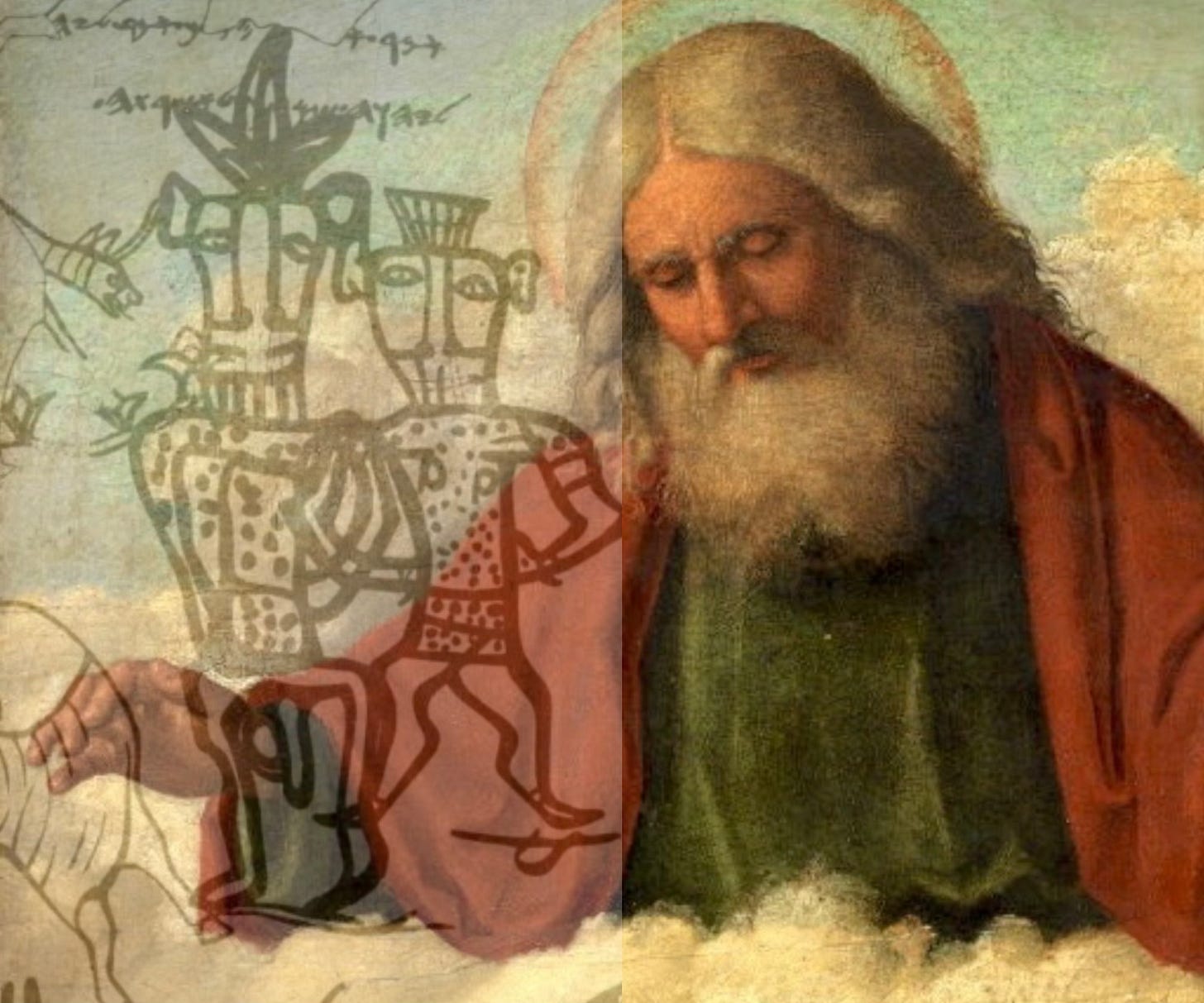

We don’t realize this because when we think of Abraham, Moses, and Yahweh, we tend to think in images inherited from familiar Renaissance paintings.

This isn’t how the people of the Bible represented themselves, however, and it’s not how they saw God.

How Renaissance Artists Rebranded Yahweh

The illustrations above fit pretty closely to the mental image most of us have when we think of Yahweh / God — even those who acknowledge, intellectually, that it’s a metaphor.

Images like these bolster Christian nationalists and others who think that Christianity is somehow a European — or even an American — phenomenon.

What then are we to think when we see how the ancient Israelites actually envisioned their God?

Let’s take a look.

Cave Paintings, or Ancient Hebrew Religious Art?

If you’re thinking the illustration above looks like rock paintings from Lascaux, Namibia, Kakadu, or the lower Pecos, you may be surprised to learn its true origin—a ceremonial jar excavated from an Israelite worship center in the eastern Sinai Peninsula.

Sinai pottery like this dates to the Early Iron Age 1200–600 B.C.E., an era that corresponds to the early kings — Saul (reigned 1021-1000 BCE), David (1000 to 962 BCE), and Solomon (962-922 BCE), found in 1st Samuel. Prophets Elisha, Jonah, and Joel were active around the year 800 B.C.E.

The inscription identifies Yahweh and “his Asherah,” so it’s pretty clear whom the artist intended to represent.

The careful observer will see that Yahweh has the head of a bull, topped by a large crown. His anatomy is overtly emphasized, underscoring themes of fertility and virility in ancient symbolism.

Asherah, beside him, has the head of a cow, a crown, and round breasts.

The image of a mother cow lovingly cleaning her a suckling calf to the left of the pair points up the traditional symbolic connection between Yahweh / Asherah and cattle.

The ancient Hebrew artist also reveals to us the relationship between this divine pair and their followers; they provide life, care, sustenance, and protection for devotees, just as a bull and cow create, protect, and nurture a calf.

Potent & Symbolic: This Works For Me

Now, I find this representation of God surprisingly compelling. After nearly 3,000 years, thinking of Yahweh this way seems fresh.

The symbolism is potent.

And yet, it’s not surprising if we look at the cultural stew from which ancient Hebrew religion emerged — the Apis bull of Egypt, as well as bulls representing deity in Mesopotamia, Minoan Crete, Roman Mithraism, and Canaanite religion (the Bull El).

Even the infamous Golden Calf episode in Exodus 32 shows how bull / cow / calf imagery was once part of El and later Yahweh worship before the Levites slaughtered the participants.

Recognizing these symbols—Yahweh as bull, Asherah as cow—invites us to see the ancient Israelites’ concept of God as embodied and intertwined with the rhythms of their world. They embodied fertility, abundance, and protection, but one needed to remain respectful.

By depicting Yahweh and his Asherah as cow-headed deities, ancient Hebrew artists tried to show us, even today, that the divine shared those characteristics.

Reflecting on the fact that these texts emerged from a culture both far more rustic and symbolically rich than our own broadens and informs my own spirituality.

Takeaway Questions

Take a moment to reflect on the images received from Western art since the Renaissance. Then take another glance at the art above — created in same the era as the books of 1 & 2 Samuel, 1 & 2 Kings, and 1 & 2 Chronicles in the Hebrew Bible.

How does that challenge or change our mental images?

Which one is more powerful to you — later, Renaissance-era image of a distant, paternal deity floating majestically in the clouds, or the earnest, primitive imagery?

Does your answer change deepening on the situation?

How do these insights challenge us regarding the rules and narratives handed down from the early Hebrew texts?

Why This Matters Now

The God we picture shapes the faith we practice.

If we continue to imagine Yahweh only as a cloud-dwelling patriarch with a flowing beard—styled by Renaissance artists rather than ancient prophets—we risk mistaking someone else's metaphor for eternal truth.

But when we recover the raw, rooted imagery of early Hebrew spirituality—like the cow-headed Asherah and bull-crowned Yahweh—we remember that the divine was once understood through fertility, embodiment, and relationship with land and animal.

And thank God, it can’t be used by Christian Nationalists; it’s not about empire, control, or whiteness.

Let’s not approach this as a simple historical curiosity. It's an invitation:

To decolonize our theology.

To unfreeze our imagination.

To find God not in the image handed to us, but in the ones we, as a culture, have forgotten.

If this resonates, please share.

If it shifts something in you, I’d be honored for you to subscribe.

I write to help us reimagine the sacred. You’re invited — and don’t forget to comment!

If you’re feeling flush, please consider tossing a coin into the tip jar. Many thanks, my friend!

Hello, Enthusiast! I’m a former military intelligence analyst turned nonprofit lifer—with two decades in housing, crisis response, recovery services, disability support, and mental health advocacy.

The G.I. Bill funded my M.Div., which I used to study world religions and contemplative practice.

You can find me on BlueSky, LinkedIn, Threads, and Medium.

BTW, If you want to know more about Asherah, here you go!

From Asherah to Andrew Tate: Why Silencing Women Is Always a Political Act

It started as a discussion about an ancient goddess

It's a critically important subject to make people more aware of too. As an additional aside, I always found it interesting that the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet aleph, means ox. Reading this in context with the Biblical phrase "I am the alpha and the omega" may harken back to a post-exile memory of Yahweh's bovine past.

A lot of common Hebrew women's names reference to cows: Leah, Deborah and Rebecca come immediately to mind. Leah, Leigh, Lee and Natalie refer to either a wild cow or having cow eyes; Deborah has its origin in the word for milk or honey and can mean to breast feed or graze in pasture, whereas Rebecca means a securely tied cow; Chloe is pasture as in grazing .The list is endless; Dora and Dorcas is deer; Gail or Ya'el is goat. Rachel interchangeably means either cow, ewe or livestock.

Basically, 3000 years ago in Israel women were called after livestock one way or another, whereas men were either beloved or the messengers of god. Draw your own conclusions.