When So Many Hateful People Wear Crosses, I Just Can’t

Are we scaring good people off with our neck wear?

Because Every Angry Politico Sports a Cross as Big as Kansas, I Need Neckwear Alternatives

If you’re one of the many Christians who is LGBTQ+ or LGBTQ+ friendly, prefer truth to lies, and don’t want to storm the capitol or set up a theocracy, you might want to rethink your neckware.

Yes, you have a perfect right to wear a three-inch gold crucifix, but now that every rabble-rousing demagogue and red-faced commentator is straining their neck muscles with ever-increasingly large crosses, you might be sending the wrong message.

You’ll never know the people who may be silently pulling away

In his op-ed, For Some, That Cross You’re Wearing May Be a Negative Symbol, Russ Dean talks about a man he met while volunteering for his son’s drum and bugle corps. After learning that Dean was a Baptist minister, he said, “Well, I’m gay. I was raised in a Pentecostal home. My parents and my church have rejected me.”

He went on to detail how he has learned to keep himself safe from people who saw him as a target, as someone they could (and should) use scripture to persecute. Experience taught that when someone “showed up wearing a necklace outside their clothing, and hanging from the necklace was a cross,” he knew that person was going to criticize, badger, and dehumanize him.

He learned to keep his distance from anyone wearing a cross.

I feel the same way. It often seems that, “the bigger the cross, the bigger the jerk.”

It’s a sleight of hand

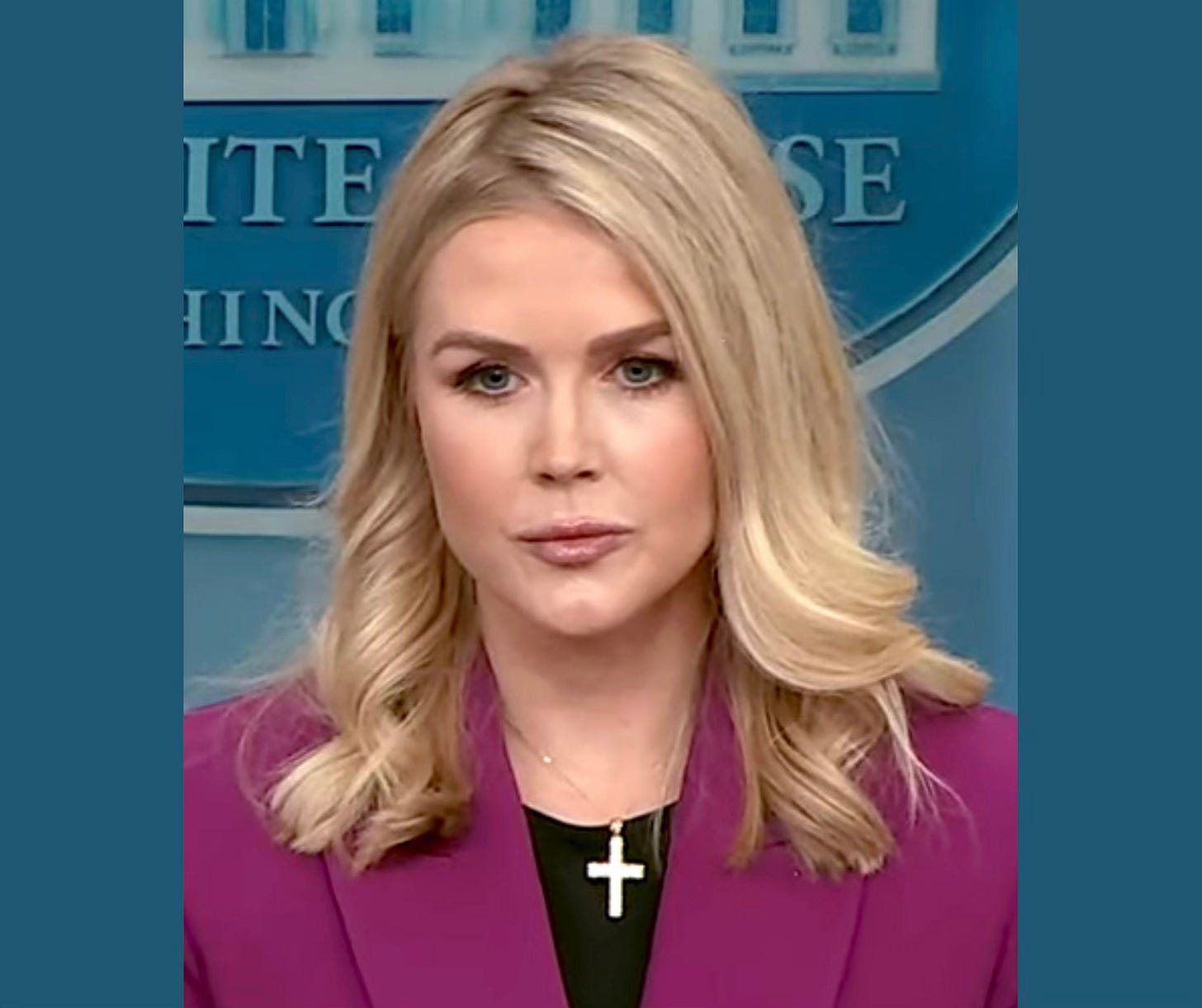

Politicos and journos chose their accessories for effect. If the cross on an announcers’ chest appeals to the audience, they’re less likely to analyze what’s being said. The wearer — like Karoline Leavitt, pictured above — is trolling for unearned trust, and often receives it.

Of course, I know there are thousands — millions — of exceptions to this rule, including my own sweet-natured pastor who collects crosses. Each passing day, she selects a specific one to set the receptive tone for her day.

Yet a set of powerful negative images about the practice has lodged itself in our collective consciousness.

I can’t speak for everyone, but will share my knee-jerk reaction. When I meet someone for the first time who is sporting a cross as big as Kansas, I assuming they’ll be overbearing, unlistening, self-serving, and in every way completely unChristian.

Sorry, that’s just my first take. I wrestle those thoughts to the ground.

Research data, however, gives a more nuanced story. Given current statistics, every cross-wearer we meet has a one-in-three chance of being either a Christian Nationalists or a sympathizer. Those numbers can rise to one-in-two, if you live in North Dakota, Mississippi, Kentucky, Wyoming, and a handful of other states.

There are a lot of nasty groups under the umbrella of Christian Nationalism. None of which I want to be mistakenly associated with.

By contrast, I’ve met some truly holy people in my time

They don’t hunger for unearned trust. They also don’t talk about themselves. Their closeness to Source is obvious. It’s palpable.

You can see it and feel it. Their manner is usually calm, cheerful, and friendly — but there’s something else going on, too. Here’s where my description begins to sound rather otherworldly, because this phenomenon is invisible, but most definitely present. It must be what artists from various religions are trying to depict with a halo.

Take the Dalai Lama, for instance

Years ago I went to a lecture by the Dalai Lama. My neighbor had tickets and asked me to keep her company. The talk was probably interesting, but I don’t recall a single word said during the lecture.

As His Holiness left the stage, we stood to gather our coats, purses, and car keys. I was asking my friend if she wanted to catch lunch when a wave swept over me. It was intense, something like the wall of heat that rushes out from house fire.

I looked around and was surprised to find the Tibetan entourage passing along the aisle right behind our seats.

The house on fire was the Dalai Lama.

Everyday Saints

This was the most profound experience like that I have had. The same thing happens all the time, however, in small ways that can be easy to miss.

I held a position for years with a group of pastoral counselors. They were all ministers of various Christian denominations — Lutheran, Covenant, Catholic, American Baptist. The organization was a prominent member of the interfaith assembly in our area, and continually worked in communion with local Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist leaders, as well as other Christians.

Pastoral counselors are a blend of psychotherapist and spiritual adviser. My coworkers all had a Ph.D. in psychology and a D.Min. in theology. They spent their lives trying to meet people where they are, and help wherever help was needed.

Much of this work was pro-bono, with people who had fallen outside society’s safety nets. The founders started working with street persons in Boston sixty years ago, and that spirit still drives their mission. I freely admit I occasionally felt concern over my personal safety with some of the clients.

Long story short, the people I worked with had put their lives and careers in service of “the good” for decades. You could feel it when you were around them. Even the most mundane meeting about insurance reimbursements or software updates felt like a shiatsu massage on my heart.

It wasn’t what these folks said. It was something about how they were — the positive effect they had on others just by being there.

Here’s what I learned from these everyday saints:

They rarely get upset, even with situations are upsetting. Even when others are upset.

They don’t care about others’ religious beliefs. They believe their mission is to heal those in mental health crisis. They consider each person’s spirituality a private and sacred thing — not for others to judge or interfere with, although they will happily speak in religious terms if the client wants them to.

In every situation they unfailingly work to help, heal, and reconcile.

Despite the counselors’ impressive degrees and personal histories, they treat every person who walks through their door as their equal.

More of this, less of that

Getting back to crosses, I want more of this, below. It’s a cross used to support inclusive language in the covenant of a genuinely welcoming and affirming congregation.

And please, let’s have less of this, below. It’s a lady confusing her religion with her politics at a “Stop the Steal” rally in Raleigh, North Carolina.

There’s been a lot of that lately.

Remember the occasional crosses at the January 6th insurrection? Dear Lord, may we never see this again.

As Christians in a world where the cross is used so frequently by those who do not share our values, we need alternatives. Not only do we to avoid being associated with political statements or destructive behavior, but — most importantly — we don’t want people, like Russ Dean’s friend at the top of this article, to assume we’re unfriendly, or even dangerous.

Some may want to drop any kind of symbolism all together, but speaking for myself, I enjoy wearing something that has special meaning to me. It’s a reminder to myself of the teachings from which I take strength.

Originally published on Medium.

Hello, Enthusiast! I’ve spent over two decades in nonprofits—housing families, supporting people in recovery, running crisis and suicide prevention lines, funding medical and mental health care, and working alongside the disability community. Former linguist & intelligence analyst for the U.S. Army; used G.I. Bill to earn an M.Div. focused on contemplative practice.

Absinthe & Transcendentalists is paywall-free for all.

Readers who opt for a paid subscription, or toss a little cash in the tip jar, keep this Substack humming. Many thanks, my friends!

Holly I like the symbol that was found above the Talipot tomb. It's the one that I use instead of a cross. https://jamestabor.com/category/talpiot-jesus-family-tomb/. It's a chevron with a circle inside.