Faith and Justice: The Mainline Ministers and Allies Who Changed America

From civil rights to LGBTQ+ equality, these Christian ministers put faith into action—challenging injustice, fighting for change, and shaping modern history.

Faith can be a powerful motivator for social change. Sadly, in recent decades it’s been used by some push back human rights in seemingly every sphere.

Christianity in particular has been tarnished by the virus-like growth of church plants and megachurches, the vacant spirituality of the prosperity gospel, the spell-casting and mythologizing of the New Apostolic Movement, the eagerness with which some churches embrace weapons, and of course Dominionism and other forms of Christian nationalism — including the increasingly influential Seven Mountains Mandate.

This mandate teaches that Christians are called to dominate seven spheres of influence in society—government, media, business, education, arts and entertainment, religion, and family—in order to “take back” the culture. It reframes the Gospel as a political conquest, not a path of humility, mercy, or justice. And it’s become the ideological backbone of many far-right churches and politicians today.

It wasn’t always this way.

Abolition, Temperance, and Labor Rights

Mainline Protestantism, which even the conservative Christian Post admits "helped create and sustain America across much of four centuries," was by and large a force for social good.

As early as the 18th and 19th centuries, mainline Protestants were deeply involved in the Social Gospel — that is abolition of slavery, temperance, and labor rights—tackling systemic injustice through Christian ethics. Their goal was to bring freedom, peace, and equal rights to as many people as possible. Ministers and their followers saw activism as an extension of their faith, advocating for a kinder, gentler, and more just society.

By the 1960s and ’70s, mainline pastors were still shaping public life, taking bold stands on civil rights, economic justice, and the Vietnam War. This was also when their influence began to wane.

That decline coincided with cultural upheaval—desegregation, gender equality, the sexual revolution, and the growing backlash to liberal Christianity. Many who once sat in mainline pews left for more conservative churches, where their worldview and behavior wouldn't be challenged.

During this time, mainline Protestants continued to engage with controversial issues—starting with poverty, race relations, and addiction, and expanding into opposition to war, environmental protection, gun control, campaign finance reform, the ordination of women and LGBTQ clergy, and support for same-sex marriage.

Conservative Christians, meanwhile, offered an easy faith through sola scriptura theology. The answers were clear, the theology non-negotiable. Racial inequality and war were not considered a hard stop. For many, stepping into those churches must have felt like a refuge from the rapid societal change of the 1960s.

The mainline denominations paid a heavy price for their focus on social justice. Their support of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was their last big win, but what a win that was. Generations have been raise with the expectation of equality under the law in the U.S. thanks to that legislation.

As we may be in the twilight of these foundational denominations, let’s explore the legacy of mainline Protestant ministers and their Jewish and Catholic allies during their last great moment—the midcentury movement for peace, racial and gender equality, and reproductive freedom.

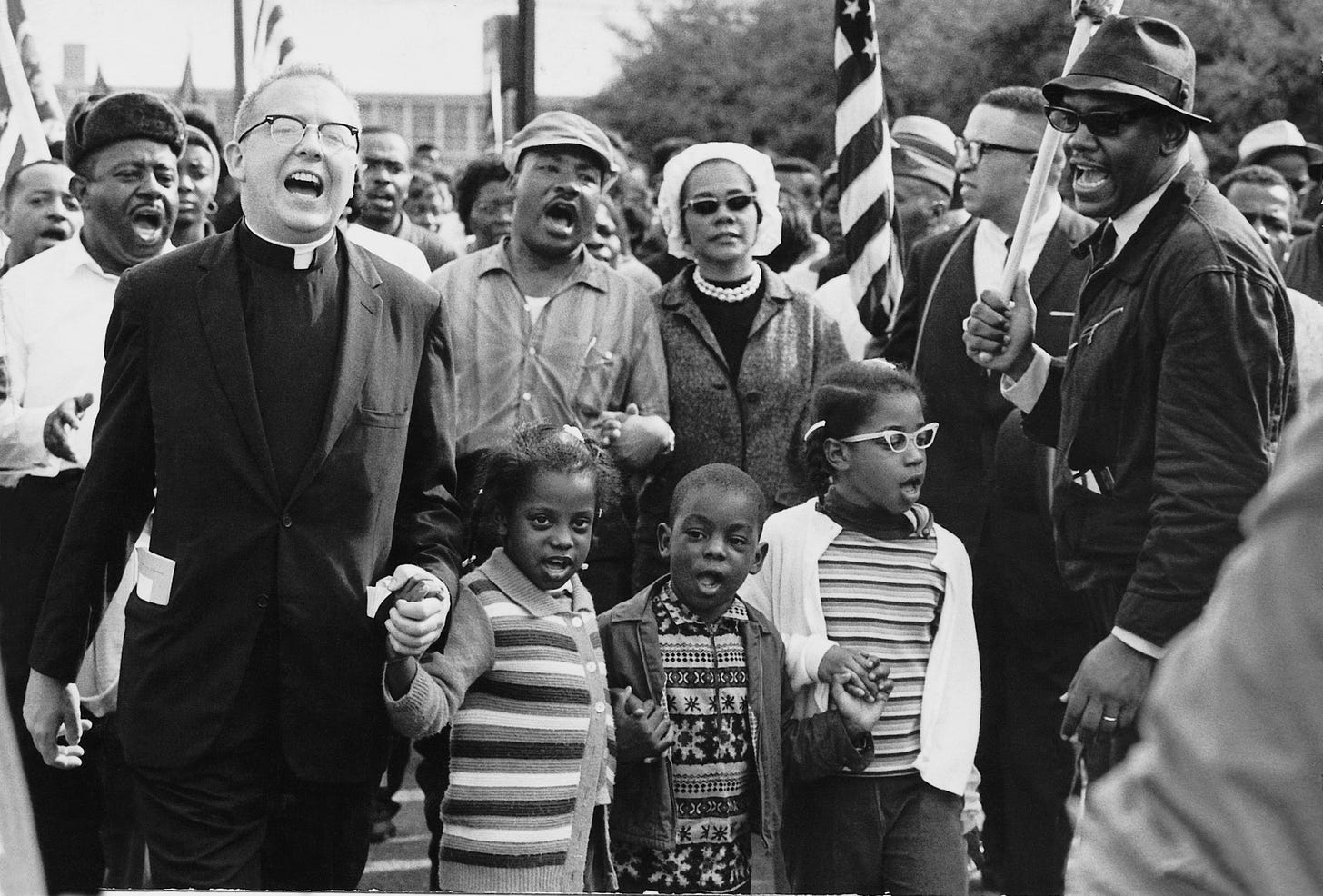

Civil Rights and the Call for Justice

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is widely recognized for his leadership in the civil rights movement, but many other ministers also fought for justice and have been largely forgotten.

Alongside King was Rev. James Reeb, a Unitarian Universalist minister who marched in Selma for voting rights. Reeb answered Dr. King’s call for clergy to support Black civil rights activists in Alabama. He was brutally attacked by white supremacists and died from his injuries. His death galvanized national support for voting rights and helped push the Voting Rights Act of 1965 through Congress.

Other Christian ministers also played critical roles in the movement:

Rev. Benjamin Elton Cox, a preacher and civil rights activist, was a key leader in the 1961 Freedom Rides, challenging segregation in interstate transportation across the South. As North Carolina's field secretary for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), he trained activists in nonviolent resistance and organized sit-ins to desegregate public spaces. Arrested multiple times, Cox was a plaintiff in Cox v. Louisiana, a landmark Supreme Court case that struck down a restrictive protest law. His work led to the integration of businesses, schools, and public facilities across North Carolina and beyond.

Rev. Virgil Wood, a Baptist minister and close associate of Dr. King, helped organize Virginia’s participation in the 1963 March on Washington and led local civil rights efforts through the Lynchburg Improvement Association.

Mathew Ahmann, a Catholic lay leader, founded the National Catholic Council for Interracial Justice in 1960 and was a major organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, emphasizing the moral imperative of racial justice in Christian communities.

Rev. Robert Cromey, an Episcopal priest, marched in Selma and was an outspoken advocate for racial justice. He later extended his activism to support LGBTQ+ inclusion within the church.

Rev. Billy Graham, though largely conservative, took a progressive stance on racial integration in the 1950s and 60s, inviting Dr. King to share the pulpit at his 1957 New York Crusade and refusing to hold segregated revivals.

Anti-War Voices: Protest from the Pulpit

During the Vietnam War, many Protestant ministers actively opposed the conflict. Rev. William Sloane Coffin founded Clergy and Laity Concerned About Vietnam (CALCAV), bringing together religious voices in protest. His sermons called for draft resistance, emphasizing Christian pacifism.

Rev. Daniel Berrigan, a Jesuit priest, became famous for his participation in the Catonsville Nine, burning draft cards in a symbolic protest against the war. Berrigan saw pacifism as a Christian imperative, believing that the gospel called for peace.

Other Christian leaders also took bold stands against the war:

Rev. Robert H. Meneilly, founder of Village Presbyterian Church in Kansas, publicly criticized the Vietnam War, serving as an observer at the Paris Peace Talks and using his pulpit to call for an end to the conflict.

The Catholic Peace Fellowship (CPF), launched by members of the Catholic Worker movement, actively counseled conscientious objectors, organized demonstrations, and encouraged Catholic leaders to renounce the war.

Sister Mary Corita (Corita Kent), a nun and artist, used her artwork to protest the Vietnam War, with pieces like "Stop the Bombing" becoming rallying cries for peace and social justice.

The Clergy and Abortion Rights

In the 1960s, some Protestant ministers became key advocates for abortion rights. The Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion (CCS), founded in 1967 by Rev. Howard Moody and other religious leaders, sought to protect women from unsafe procedures by discreetly connecting them with safe medical providers. By 1973, CCS had referred thousands of women to competent doctors, playing a critical role in shifting public attitudes before Roe v. Wade.

Notable clergy involved included:

Arlene Carmen, worked alongside Moody as an administrator at Judson Memorial Church, was instrumental in vetting abortion providers to ensure women received safe medical care. She personally visited clinics, pretending to be pregnant to assess the cleanliness, ethics, and pricing of each provider. Her work helped establish the CCS’s trusted referral network, ensuring that women were not exploited or subjected to unsafe procedures. Carmen also played a critical role in legislative discussions when New York moved to legalize abortion, advising against unnecessary restrictions such as requiring women to meet with clergy before obtaining the procedure.

Rev. Robert Hare, a Presbyterian minister who counseled women facing unwanted pregnancies with compassion and discretion, helping them navigate restrictive abortion laws by connecting them to safe providers. He was charged as an accessory to abortion, sparking national outcry from religious leaders who argued that abortion counseling was a protected pastoral duty. Though his charges were eventually dropped after Roe v. Wade, his case underscored the risks clergy took to ensure reproductive freedom.

Rev. Charles Landreth, an American Baptist minister who boldly preached on abortion from the pulpit, calling for compassion and justice. He emphasized the Baptist principle of "soul freedom," affirming that individuals have the right to moral and bodily autonomy, with guidance from God—extending this belief to a woman's right to make decisions about her own body. He also cited scripture to argue that life begins at birth, reinforcing the idea that reproductive choices should be left to individual conscience.

These ministers saw abortion access as a moral responsibility, ensuring that women had safe options rather than life-threatening alternatives. Their advocacy played a role in paving the way for Roe v. Wade.

LGBTQ+ Inclusion

Protestant clergy also led the charge for LGBTQ+ inclusion, beginning in the late 1960s with Rev. Troy Perry. Perry founded the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) in 1968, creating a space for LGBTQ+ Christians to worship without fear of rejection. MCC became a lifeline for queer Christians at a time when many churches were openly hostile to them.

Other affirming clergy followed.

Following Perry’s leadership, Rev. Elder Freda Smith became the first woman ordained in MCC and worked tirelessly for LGBTQ+ rights within Christian communities. Smith was the last speaker at the end of a march on June 25, 1971, at the California State Capitol to legalize homosexuality in private between consenting adults. Her speech that day is included in “Speaking for Our Lives: Historic Speeches and Rhetoric for Gay and Lesbian Rights (1892-2000).”

Rev. Nancy Wilson, who later became MCC’s moderator, played a crucial role in expanding the church’s reach, ensuring that LGBTQ+ people around the world could find affirming spaces to practice their faith. She’s the author of Our Tribe: Queer Folks, God, Jesus, and the Bible.

Rev. Mel White came out in 1994 after being instrumental in the evangelical resurgence. After serving evangelical Christians as a pastor, seminary professor, filmmaker, and communications consultant, ghostwriting autobiographies for prominent Religious Right leaders, such as Revs. Billy Graham, Jerry Falwell, D. James Kennedy and Pat Robertson, he came out in 1994. White and his partner, Gary Nixon founded Soulforce as a challenge to homophobic rhetoric within Christian institutions. White’s 1995 autobiography, Stranger at the Gate: To Be Gay and Christian in America, received worldwide acclaim and is still in print today.

In 2003, Rev. Gene Robinson became the first openly gay bishop in the Episcopal Church, sparking controversy but marking a new era of inclusion. His leadership symbolized the church's slow but steady march toward LGBTQ+ equality.

Why This History Matters Now

The progressive Protestant tradition has never been about wielding power for its own sake—it has been about using faith to uplift, liberate, and protect the most vulnerable. But today, regressive religious voices hold disproportionate influence, backed by political power, media networks, and vast financial resources.

Their goal is to control people, not free them.

Mainline Protestant denominations—once a dominant force in American religious life—have seen their numbers decline since the 1970s. However, their legacy of justice, activism, and ecumenical collaboration remains a powerful force for good.

Jesus would have called those who seek power and domination on the carpet for aligning themselves with political influence instead of the people. And that’s why we need progressive ministers today more than ever.

The good news? They’re out there. But they don’t have the institutional backing that their conservative counterparts enjoy—megachurch funding, vast media networks, well-organized political alliances, lobbying groups, and deep-pocketed donors supporting their influence in public discourse and policy-making. That’s where we have to come in.

We must seek them out, amplify their voices, and support their work. Whether it’s through donations, sharing their messages, or simply showing up, we have the power to ensure that progressive Christian activism continues to thrive.

Faith can still be a force for justice. Let’s make sure it is.

Hello, Enthusiasts! This is your friendly former military intelligence analyst with an M.Div. I’ve spent a few decades in nonprofits — getting families into housing; supporting clients in recovery; providing crisis & suicide prevention services; funding medical, dental and behavioral care; and partnering with the disability community.

If you’re feeling flush, please consider tossing a coin into the tip jar. Many thanks, my friend!

Look me up when you’re on BlueSky, LinkedIn, Threads, or Medium.

Interested in reading more about the intersections of faith, history, and culture? Subscribe for more stuff like this.

So good to see this--all these names/people/EFFORT and love noted. Lots to go deeper with here--thank you!!